- Home

- Jane Petrlik Smolik

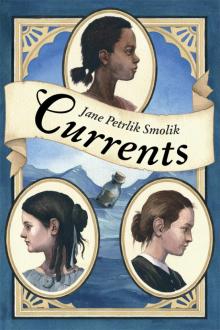

Currents

Currents Read online

Text copyright © 2015 by Jane Petrlik Smolik

Illustrations copyright © 2015 Chad Gowey

All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. Charlesbridge and colophon are registered trademarks of Charlesbridge Publishing, Inc.

Published by Charlesbridge

85 Main Street

Watertown, MA 02472 (617) 926-0329

www.charlesbridge.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Smolik, Jane Petrlik, author.

Currents / Jane Petrlik Smolik.

pages cm

Summary: In 1854, eleven-year-old Bones is a slave in Virginia who sends a bottle holding her real name and a trinket from her long-lost father down the James River—the currents carry it far away, ultimately uniting the lives of three young girls.

ISBN 978-1-58089-648-1 (reinforced for library use)

ISBN 978-1-60734-863-4 (ebook)

ISBN 978-1-60734-900-6 (ebook pdf)

[1. Slavery—Fiction. 2. African Americans—Fiction. 3. Identity— Fiction. 4. Social classes—Fiction. 5. Isle of Wight (England)— History—19th century—Fiction. 6. Great Britain—History— Victoria, 1837–1901—Fiction. 7. Immigrants—Fiction. 8. Irish Americans—Fiction. 9. Authorship—Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.S66459Cu 2015

813.54—dc23 2014010491

Printed in the United States of America

(hc) 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Illustrations made with watercolor on Arches watercolor paper

Display type set in Stempel Garamond AS

Text type set in Stempel Garamond AS, ITC Zapf Chancery,

Metroscript by Alphabet Soup Type Founders, and Mostly Regular by Jonathan Macagba

Color separations by Colourscan Print Co Pte Ltd, Singapore

Printed by Berryville Graphics in Berryville, Virginia, USA

Production supervision by Brian G. Walker

Designed by Martha MacLeod Sikkema

To Karen Boss,

for helping me bloom

Contents

Bones—Virginia, Autumn 1854

Lady Bess—Isle of Wight, August 1855

Mary Margaret—Boston, November 1856

Epilogue

Author’s Note

Acknowledgments

Source Notes

Learn More

BONES

Folks along the James River swore it was because of the tobacco-plant flowers. Queenie, the cook, was certain it was due to all the roses that grew in Old Mistress’s gardens. Whatever the reason, the honey that came from Stillwater Plantation’s hives was considered the finest in all of Virginia. Friends and neighbors looked forward to a jar at Christmas and on special occasions.

Every other month, Bones covered herself up in the special bee suit that Queenie had made for her and carefully carried her bee-smoker pan to the hives. She slowly filled wide-mouthed bottles with the golden nectar. Every now and again Queenie would slip a jar of the sweet treat to Bones, who would take it home to Granny and Mama.

Bones would always sneak the empty bottle back to the kitchens. Except for the one she saved—that one she kept just for herself.

Chapter One

VIRGINIA, AUTUMN 1854

Bones was too young to remember the day her pappy had been sold off to another plantation, but she remembered everything about how she learned she was the personal property of another human being.

“Took you so long to sweep the kitchen, you need somethin’ else to eat to keep you goin’,” fussed Queenie, the cook, as she placed an extra piece of cornbread in front of Bones. The little girl ate it carefully, so as not to drop crumbs on the corncob doll hanging from her neck by a rawhide string.

“You’d better go now and wake up Miss Liza. I suspect you be doin’ all sorts of things today. Looks like the sun’s gonna be shinin’. And stop jigglin’ that foot of yours, or Old Mistress tie you up in a chair again!”

Queenie had been the head cook since Master Brewster bought her years ago and brought her to Stillwater Plantation. She had been born on the Smiths’ farm a few miles down the river and had learned as a child to prepare tasty pork, chicken, pies, and fresh greens. Master Colonel Sam Smith sold her for one thousand dollars to the Brewsters solely on her reputation in the kitchen. They sold her on the condition that her new family promised not to beat her, and if she ever acted so badly that she had to have a whupping, her new master would bring her back and drop her off in the yard where he got her.

Every morning when Bones appeared in the kitchen, Queenie was cleaning Master’s boots, shoes, and sword, and making his coffee before starting breakfast.

Staring out the Brewsters’ kitchen window, Bones had a clear view past the big house and the kitchen gardens to the rows of unpainted cabins. She lived in one of them with her granny and her mother, Grace. Theirs was the farthest one away, and from their door, a weedy dirt path led straight to the fields that sloped gracefully down to the James River. Granny and Mama were field hands, and left every morning before dawn to work the long rows of tobacco, corn, wheat, and cotton. Each cabin had its own garden patch in the back where the slaves were allowed to grow extra food. At night or on Sunday afternoons, they could tend their own rows of cabbage, lima beans, onions, potatoes, black-eyed peas, and collards. If one person had too many collards one week, they would trade with someone who had too many lima beans.

Stillwater was one of a handful of old plantations that sprawled out along Virginia’s lower James River. Built with bricks that had been fired on the property and shaded by wide porches framing three sides, it sat at the end of a gravel drive lined with oak trees and mountain laurel. The back porch, which overlooked the river, stretched across the entire length of the house and was held up by eight fluted white pillars. Lounge chairs, tables, and settees were placed neatly about, and magnolias planted around the house brushed against the roof and spilled their fragrance into the soft Virginia air. In the front yard, carefully clipped boxwood hedges surrounded three levels of terraced gardens, built to show off the Mistress’s rosebushes.

During the sweltering summers, the river created a welcome breeze through the house. Deep forests at the back of the property provided some of the wood to keep the stoves and fireplaces burning all winter, and the acres of fields kept the slaves busy planting and picking crops. Nine hundred peach trees were planted in a single row like a living fence around one of the backfields. Peach trees grew like weeds in the fertile soil, and field hands cut down one hundred trees a year to use as firewood. In the spring, one hundred new saplings were planted to replace the ones that had been cut.

Master Brewster strolled into the kitchen house and let the door slap shut behind him, tilting his head up to breathe in the sweet fragrance of molasses and chopped peaches.

“Have you woken up Mistress Liza yet?” he asked Bones. His sturdy frame filled the doorway, and his riding boots clacked on the freshly swept floor. As on most large plantations, the kitchen house was a separate building located off to the side to keep the main house cooler and reduce the risk of fires.

“No, Masta,” Queenie said, sweet as the shoofly pie she’d begun to assemble. “Bones just goin’ up now.”

Master Brewster shook the sweat off his large straw hat and leaned down to tug at the girl’s braids. Mama fixed them every day to cover her ears that seemed to sprout straight out from her head. But it never worked. Granny said those ears made her special because she could hear extra good.

“And what is this?” He pointed at the old corncob wrapped in a handkerchief hanging from her neck.

“My baby doll,” Bones answered.

“Ah! Yes, now I see that.” He looked at the plain corncob, with no face

or clothes. “And does your baby doll have a name?”

“Lovely. Her name’s Lovely.”

“Well, that’s a mighty fine name for her,” he said with a chuckle. “Is this another baby doll?” he asked, pointing to the peach pit that she rubbed between her fingers.

“No, this here’s a heart.” She smiled up at him. “My pappy carved it for me and give it to me when I was born. I like how it feels.”

“Aha. I see. Well, now you make sure Miss Liza does her reading today,” Master instructed. “She can’t just play with the animals, pick flowers, and daydream.”

Bones carefully balanced the breakfast tray the cook had prepared for her young mistress and walked slowly out the back door, calling out behind her, “Oh yes, I will, Masta Brewster. Don’ you worry ’bout that.” The s-sound in “Brewster” whistled through the gap between her two front teeth. She went down the short path to the big house and up the back staircase, the one the slaves used. Carrying her mistress’s breakfast tray upstairs was the first duty of the day, and sprinkling her bedsheets with refreshing lilac-scented cologne was the last duty at night.

Chapter Two

For the most part, Bones didn’t mind her life as Miss Liza’s companion. It was certainly much easier being a house slave than a field slave. She had been brought up to the big house when she was five to keep Miss Liza company, and in the six years that followed, the girls had spent countless hours exploring the plantation and playing games. Liza’s sister, Jane, was fifteen years old and found plenty of companionship with twin sisters her age who lived on a farm down the road. There was just enough difference in the Brewster girls’ ages that Liza needed a playmate of her own. The younger of the Brewster daughters loved to play in the fields and run with the dogs down by the river and on the edge of the woods. She and Bones would gather up pinecones, twigs, fluffy mosses, and little pebbles and build castles with stick bridges and roads that they dug through the soft dirt.

In the afternoons, when the heat drove them back into the big shuttered house, Bones would go to the kitchen and fetch Liza a cold glass of fruity iced tea. Liza always insisted that Queenie make a glass for Bones, too. Then Bones would sit and wave a tasseled fan back and forth over her little mistress while Liza sat with her spelling books and blocks and studied her reading and writing. This was usually done with a great deal of sighing and fiddling, as Liza was not fond of studying. Hanging on Liza’s wall was a large, colorful map of the United States of America. Master had stuck a red pin onto the spot to mark the location of Stillwater Plantation, and Liza enjoyed having Bones play student to her geography teacher.

Virginia.

Virginia looked like an old snail trying to slither away from a hungry fox. Liza had taught Bones which way on the map was north, south, east, and west. Just south of Virginia was North Carolina. Long and thin with a tail pointing out west—sneaking into Tennessee. Below that, South Carolina, and then Georgia and Florida.

Bones kept to herself why she was so interested. She reckoned her pappy was in one of those lands, and she planned on finding out where. Her mama and granny didn’t know where he’d been sold, but she figured it couldn’t be north of here. The Northern states didn’t take to slaveholding. If the whispers in the fields were right, the North was going to set all the slaves free or else. She needed to be ready either way. The more she learned about mapping, the better prepared she’d be to find her pappy and reunite him with Mama and Granny. It was going to be a fine day when they were a family again. She had had her plan in place for almost a year now, ever since Liza had begun teaching her the mysteries of the map.

“What do all those lines goin’ every which ways mean?” Bones had asked one day, pointing to the letters on some blocks.

“They are the letters of the alphabet, Bones. You’ve heard Daddy talk about the ABCs. Well, those are the first three letters of the alphabet. See? Here they are. This is an A. The first letter,” Liza had said.

Bones had run her finger up one side, slowly down the other and then connected the two in the middle.

“That’s an A?” she had asked, eyes wide.

“That is an A. It sure is. And this is a B. The first letter of your name begins with the letter B,” Liza had explained.

“These the same lines that’s on the map?” she had asked.

“The very same.” Liza had drawn two slanted lines connected at their base. “That’s a V. Just like the first letter of Virginia. See here on the map. I taught you where Virginia is.”

Bones had looked at her like she had spoken a miracle. It had long ago occurred to Liza that it was more fun playing teacher than simply studying boring books, and in Bones she had an eager student. So afternoons that summer Bones spent learning how to read and write the alphabet, and how to read simple books made up mostly of two-syllable words. She knew that learning how to read the words on the map, instead of just learning the shapes of the states, could only help her with her plan.

Chapter Three

Bones figured that when the Lord was passing out kindness in the Brewster family, he used it all up on Master and his two daughters, because he sure didn’t have any left for Master’s wife, Old Mistress Polly.

“Musta been a terrible day the day she was born,” Granny always sputtered, slowly shaking her head back and forth. “Musta been a dark storm or somethin’.” Granny was wiry and thin from working the fields, her hair pure white, and Mama often wondered aloud if the Brewsters were ever going to bring Granny in to work in the big house. Bones worried that they were just going to keep her working in the fields till she dropped dead one day over a tobacco plant.

Old Mistress Polly’s disposition was as sour as a briny pickle. While her husband was tall and graceful, she was small and plump, with narrow, gray-green eyes that rested inside little slits under her short forehead.

Sometimes the house slaves would look up to see her shadowy figure on the wall. They knew she was lurking around the corner, waiting to catch them not doing their chores so she could lurch out with her hickory stick and smack their hands. Many of them took to calling her Wolf Woman behind her back because of her slanty, gray-eyed stare, and everyone tried to stay out of her way to avoid her fits of ill humor. The Brewster sisters never talked back to their mother, and like everyone else, they preferred the company of their father.

It was a quiet autumn afternoon, and a river breeze pushed through the shutters’ open latticework. Liza and Bones were excited. The newest edition of Merry’s Museum Magazine had arrived that morning. Liza had explained to Bones that it was the most popular magazine among children everywhere. It was filled with stories for children about people having daring adventures. Liza’s favorite section every month was the puzzles and letters from children to Uncle Merry, but Bones was mesmerized by the stories about foreign lands and the exotic animals that lived there.

“Finish writing the sentences I’ve given you, and you may look through my new Merry’s,” Liza instructed Bones.

Bones flew through her assigned work, wondering all the while to herself: What magic is in this month’s magazine?

She wasn’t disappointed. There was a black-and-white engraving of waterfalls in New York, and one of a Christmas tree with little white children dressed in fancy clothes sitting under its branches hung with glowing candles, candies, and small toys.

Bones’s heart nearly pounded through her chest when she turned a page and read a title: “Africa: Dr. Livingstone’s Journeys and Researches in South Africa.” An illustration on the opposite page showed a canoe with seven or eight men being thrown into the dangerous waters, their arms flailing as a monster beast rose from the water. The words beneath the picture read: Boat capsized by a hippopotamus robbed of her young.

“Miss Liza? What is this word?” Bones pointed at capsized.

“‘Capsized,’ Bones. It means to overturn in the water.”

“Oh my,” Bones whispered.

It got better. The next story she found was titled

“Africa and Its Wonders.”

Lord, if she could only show this to Granny.

“‘The trees which adorn the banks of the Zonga are magnificent,’” she read, hesitating to sound out the last word. “Miss Liza, Africa—she’s a powerful, beautiful place,” Bones finally announced.

Liza laughed. “Yes, I suppose it is.” She suddenly tilted her head toward the bedroom door when she heard the hall floor creak.

Bones quickly put aside her writing paper when she heard familiar steps stealing down the hallway outside Liza’s bedroom. By the time the door thrust open and Old Mistress Polly burst into the room, Bones had already picked up her fan and was busy shooing flies away from Liza’s face.

Old Mistress’s left eyebrow flew up. “How is the reading coming along?”

“Very well,” Liza replied. But worry lines pinched her forehead, and she fiddled over her book as her mother’s glare bored through her.

Old Mistress’s eyes swept the room, landing on Bones’s writing pad. When she walked over and picked it up, Bones broke out in a sweat, and her fan began to shake.

“What is this?” Old Mistress asked, her breath warm on the back of Bones’s neck.

Before she could answer, Liza spoke up. “Some old papers of mine.”

The Wolf Woman squinted harder at Bones’s childlike letters, so different from Liza’s more graceful, swooping words and curly letters.

Bones looked down and saw her spelling book and the map on which she had printed the states and each state’s capital poking out from under her skirt. Mistress suddenly yanked the little black girl up by her arm and snatched the papers from beneath her. Bones’s beginning letters were carefully scrawled on page after page next to Liza’s.

She did not fully understand why, but she knew in that moment that she was in fearsome trouble. She picked up her fan again and began furiously waving it next to Liza. In mid-swoop, Mistress ripped it away and began swatting her on the head with it.

Currents

Currents