- Home

- Jane Petrlik Smolik

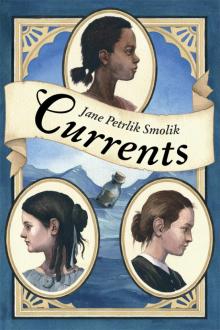

Currents Page 12

Currents Read online

Page 12

There had been no word from him in over a month, but in his last letter he wrote that he would be in Zanzibar soon and he still expected to be back on the Isle of Wight by the first of March.

So when a letter with no return address arrived one day for Lady Bess Kent with the postmark too smeared to read, she tore it open expecting to find a note from her father. A single piece of paper with the letter S on the front fell out of the envelope. She flipped the sheet over. On the back it read, “S. For safe.”

MARY MARGARET

The bottle was lost in the English Channel when Chap Harris’s boat was destroyed. From there, the North Atlantic Drift, a powerful warm ocean current that merges with the Gulf Stream, picked it up. Currents, like giant rivers, move constantly through the world’s oceans. Before this was understood, sailors would stop their boats for the night, only to wake up bewildered when they found themselves miles away from where they stopped. Two identical objects released at the same location at the same time, affected by storms and winds, can end up in dramatically different areas.

If the bottle had entered the water a few hours later or a few miles farther out, or if an unexpected storm had struck during its journey—it could have very well ended up in Africa or India or almost anywhere in the world where land touches the sea.

Chapter Thirty-Four

BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, NOVEMBER 1856

“When you’re done, I’ll have you drop off Mrs. Dartmouth’s shoes at her house on your way home,” Mr. Eaton said, popping his head between the red velvet curtains that divided the ironing and storage area from the front of his shop.

“I’m finishing up now, sir,” Mary Margaret answered, placing her hot iron down on its pad to cool. She’d pressed three dozen shoe- and bootlaces, and then threaded them back into their respective shoes. It was usually only two hours’ work four days a week, but Mr. Eaton paid her eight pennies a week for it, and there wasn’t much else a twelve-year-old Irish girl could do for work in the city of Boston. And besides, Elton Eaton’s Boot and Shoe Repair Shop was close to home on Beacon Hill, just four blocks from the basement apartment that Mary Margaret shared with her parents and younger sister.

She didn’t mind the work. Unless she peeked out, she couldn’t see the customers from where she labored behind the curtain. To pass the time, she made a game of guessing who they were when they entered the shop—by the sound of footsteps, the scent of cologne, or the dead giveaway of their voices. Some were easy, like Miss Beatty with her musical voice like a flute, or Mr. Finn with his big donkey voice that mismatched his elf-sized feet.

She pulled yesterday’s newspaper from the pile that Mr. Eaton had next to his desk in order to wrap Mrs. Dartmouth’s shoes, but stopped when she noticed three paragraphs circled in red. The first item was titled “Lonely Hearts Advertisements.”

She skipped down and read the second circled paragraph. “Widower, forty-four years of age who does not drink or smoke seeks warmhearted lady for purpose of marriage. Owns small shop with living quarters above. Signed—Boston Shoe Man.”

Mr. Eaton must’ve made the marks on the paper, Mary Margaret realized. Several columns below he had circled: “Upright young lady looking for a warm hearth and a warm heart. Not the least pretension of beauty, but I am patient and gentle and have all my own teeth. Favorite pastimes—reading and correspondence.”

“Oh no!” Mr. Eaton reached over and took the newspaper from Mary Margaret. “Please use tissue paper until I tell you differently. I’ve been saving the newspapers lately.”

“Yes, sir,” she said and reached for a sheet of tissue paper. Mr. Eaton was an orderly man. Every morning he read that day’s newspaper from cover to cover, and then set it neatly on top of the growing pile. “Are you saving them to kindle the stove fire?” she inquired, wondering if he’d mention the Lonely Hearts ad.

“No,” he said, smiling. “For something else—something of a personal nature.”

Mr. Eaton is going to get himself a new Mrs. Eaton, Mary Margaret thought excitedly. She decided not to ask any more. Ma constantly warned her to remember her place.

Mary Margaret knew that poor Mr. Eaton had been all alone since his dear wife had passed away three years earlier. They had no children and he had no other relatives. At the end of the day, he closed up his small shop and retired to his apartment on the second floor. Mary Margaret didn’t think he spoke a word to another soul until the next day when he came back downstairs. He seemed to enjoy chatting with his customers, and she thought he had come to appreciate her abilities and sense of humor.

“You have common sense, Mary Margaret,” he often said to compliment her. “That’s a quality that seems to be in dwindling supply.”

Mary Margaret took one last look at the tiny back room to be sure she left the iron on its pad and everything in order before closing the red drapes behind her. The front of the shop wasn’t much bigger than the back room. The shoemaker loved to read and was a student of history. Along with his tools and shoe bench, stacks of books lined the walls, with still more neatly piled on the floor. There were books about how to identify birds by their song, how to recognize a silversmith’s mark, and by what manufacturer a china platter had been made. And there were dozens more books, many about the faraway places that Mr. Eaton hoped to visit someday. It seemed as if every question Mary Margaret had, Mr. Eaton had a book that held the answer.

“Shall I come back later today, Mr. Eaton?” she asked. “Do you have anything else for me to do?”

“No, no. You can leave for the day. I have company coming soon.”

“I noticed that you bought some flowers for your tea table,” she said, fishing for more information.

Mr. Eaton laughed. “Very observant. It is a lady I’m expecting. Her name is Daphne Cummings.”

“Oh, Mr. Eaton,” she cooed. “’Tis a lovely name. She sounds like a beautiful spring flower!”

“Well, we shall see. She is coming over in an hour for tea,” he said.

“Does she live close by, sir?” Mary Margaret asked.

“Several blocks from here with her ailing mother, I’m afraid. That’s why we haven’t met before. Her mother isn’t long for this world, and she doesn’t want to upset her by bringing around a fellow. So I can’t visit her at her home just yet.”

Mary Margaret thought about that and said, “I would think her mother would be glad to know that when she left this world her daughter was going to have a fine man like you to keep company with her, if you don’t mind me saying so, sir.”

Mr. Eaton blushed a little. Then he said, “Well, we’ll just have to see. But you’d better be getting off. Mrs. Dartmouth will be looking for her shoes. Go along now.”

She tucked Mrs. Dartmouth’s shoes under her arm and headed out into a light, wet snow, pulling her frayed coat close around her neck. The crown of her hair, still damp from sweating over the iron, froze in little tufts that stood up like waves.

Reaching the top of the hill, she rapped the brass knocker on the Dartmouths’ door. She was getting ready to leave the package inside the front vestibule when a beefy hand grabbed the back of her dress and pulled her backwards into the street.

Chapter Thirty-Five

“And what do we have here? A little mick out stealin’ from the good folks of Beacon Hill?” A booming voice split through the cold air.

“Put me down,” Mary Margaret hollered, kicking her feet. “I’m not stealing anything!”

“Sure you’re not! What do you have there in your hand? Let me see that package,” the man demanded. She could see now that her assailant was a police officer with a nasty-looking club hanging from his belt. He put her down, but kept a tight grip on her arm and eyed her with a look of mistrust so true that it took her breath away.

Before Mary Margaret could say another word, the door swung open, and Mrs. Dartmouth rushed out. “Oh, officer! Oh, my goodness. What in heaven’s name is going on here?”

“See here what I found? Little Irish r

iffraff trying to steal this package from you! Caught her red-handed.” His face lit up, proud of his catch. Mary Margaret figured he was hoping the lady would slip him a coin for his troubles.

“Oh, Officer Dyer, no. You’ve made a mistake. This child works for Elton Eaton. She’s delivering my shoes, not stealing them!”

Officer Dyer—for that was the name on the brass name tag, Mary Margaret now noticed—looked suddenly deflated.

“An Irish girl?” he asked, incredulous.

“Well, yes. You don’t need to be an Englishman to deliver shoes, for heaven’s sake,” Mrs. Dartmouth replied haughtily. She took the package before disappearing back inside her house.

Mary Margaret looked down at her feet, and Officer Dyer glared at her.

“I’ll escort you out of the neighborhood,” he finally said. “If you’re not doing errands for someone, the likes of you don’t belong here.”

“But I live in this neighborhood,” she said, trying not to sound too defiant.

“Really, now?” His eyebrows rose up. “Well, let’s see where, shall we?” Mary Margaret started to walk to her apartment in silence, with Officer Dyer following closely behind, slapping his club against the palm of his hand. The longer he slapped it, the more annoyed she became.

Who does he think he is, the King of England? she thought.

Halfway up the street she stopped in front of a brownstone, turned around, looked him straight in the eye, and said in her most polite voice, “Thank you officer, for escortin’ me home.”

“Why you . . .” But no sooner had he reached out and sunk his fingers into her arm than a stronger arm pulled him away.

“See here, what are you doing with this girl?” George Bennett was not pleased to see commotion in front of his house as he arrived home from work.

“Da!” Mary Margaret said when she saw her father rushing up behind Mr. Bennett. It was just past five o’clock, and Tomas Casey, Mary Margaret’s da, who worked in Mr. Bennett’s shipyard, was also returning home.

“This is my daughter, officer,” Da sputtered, hiding his balled fists in his pockets.

“See here,” Mr. Bennett continued. “What in heaven’s name is going on here? Officer? Explain yourself.” Mr. Bennett placed himself in front of the policeman, and Mary Margaret rushed into her da’s arms.

“Sorry, sir. The girl says she lives here!” Officer Dyer bellowed. “And this fellow now says he’s her father. Some kind of father-daughter swindle for sure. It won’t be the first I’ve seen from the likes of these people.”

“They do live here. I’m George Bennett. This is my house. The Caseys live below stairs in my home and work for me. Has young Mary Margaret committed some legal offense, sir?”

“You got an Irish family livin’ in your home?” the policeman asked, screwing up his red face.

“I do, and what of it?” Mr. Bennett snapped.

“I see. Well.” Officer Dyer put his club back in his belt.

“Again I ask you,” Mr. Bennett said, clearly agitated, “has the girl committed any offense besides walking in her own neighborhood?”

“Well, no. No, I just assumed . . .” The street in front of the house was growing busier with people returning home from work, and Mr. Bennett didn’t like the attention the incident was drawing.

“Well, all right, then,” Mr. Bennett said. “Let’s break this up and go back about our business. I, for one, am ready for my dinner. Good night. See you in the morning, Tomas.” He patted Da on the shoulder and went inside.

Officer Dyer and Da, both breathing heavily, stared at each other for a long moment until finally the policeman hissed under his breath, “Catch the girl so much as spittin’ on the sidewalk, and I’ll clock her.” He gripped his club and gave it a menacing little shake.

Da didn’t blink, but Mary Margaret could see his chest heaving under his coat.

“I hear ya, Officer,” was all he said between tightly clenched teeth.

“It’s all right, Da—he didn’t hurt me.” Mary Margaret pulled at his sleeve to come inside, shuddering at how tense his body was beneath his jacket.

Chapter Thirty-Six

The next day, Mary Margaret and Louisa Bennett sat on the Bennetts’ parlor-room carpet with a large crate of doll clothes, carefully picking through the box and examining each piece. Boots, the Bennetts’ cat, stretched out next to them, occasionally flicking her long black tail or licking the white paws she was named for.

“My dolls don’t wear this anymore,” Louisa announced, holding up a little black wool cape. She put it in the stack she was making to give to Mary Margaret. Mary Margaret’s doll had just one cotton dress that her mother, Rose, had made from an old tea cloth. Now, she thought, my doll will have a wardrobe fit for a queen!

“This one has a little tear in it.” Louisa scowled at a blue flowered dress.

“Oh, I don’t mind at all. My ma taught me how to sew long ago. I can stitch that up like new,” Mary Margaret said, quickly adding it to her growing pile.

As the girls were sorting, Louisa’s parents sat with their coffee, watching their only child play. “George, I’ve been thinking, and if the President of the United States can have a Christmas tree in the White House this year, then so can we have one here,” Mrs. Bennett said to her husband, leaning in closer to him. “The papers say Mrs. Pierce is going to set one up in the East Room and decorate it with holly and pinecones and sprigs of green, and she and the president have invited groups of children to visit and sing ‘Hark, the Herald Angels Sing’ around the tree.”

Mr. Bennett looked over at her, squinting through his wire-rimmed spectacles, and said, “Franklin Pierce won’t be president much longer, my dear Aurelia. All his talk against freeing the slaves in the South has cost him the election.”

“It would be so festive in our parlor’s bow window,” Mrs. Bennett mused.

“My dear,” Mr. Bennett sputtered. “I want our daughter to know that Christmas is about a great deal more than sitting around a dead tree and eating candy out of an old sock.”

She leaned over and rested her hand on his. “Oh, please, George? What harm would it do, dear?”

“Oh, Papa,” Louisa piped in. “We could have little candles and even candies on it. I think it would be so very grand!”

Mrs. Bennett stood up and went over to the window, scooping up Boots and absentmindedly scratching behind the cat’s ears. “Of course, I know many people are still dead set against it. They want it to remain a simple, solemn day. Frances Lowe next door feels very strongly about it.”

“Frances Lowe hasn’t an ounce of good cheer left in her for anything,” Mr. Bennett grumbled. “She is against everything fun. Cranky old woman, if you ask me. I tell you, I feel sorry for her students at that girls’ school.”

“George, be kind.” Mrs. Bennett frowned and glanced over at the girls. “Frances is an excellent teacher. Poor dear, since her husband died all she has left are her pupils and her son, Lucas. You know he was only sixteen when he sailed off two years ago to California looking for gold. My word, he was just a boy! Frances is hopeful he’ll be back any day, perhaps before Christmas.”

“You know what they say, my dear.” Mr. Bennett looked up at his beautiful wife. “God doesn’t give anyone more than they can handle.”

“On the contrary, George,” she said with a sigh. “I see people all the time who have been given more than they can handle.”

Mary Margaret’s head popped up from sorting doll clothes, and she asked, “Excuse me, but did you say that Lucas Lowe will be home for Christmas?”

Louisa also looked up and said, “Will he, Mama? He’s been gone forever.”

Mary Margaret and Louisa had tagged after Lucas every chance they’d gotten when he’d lived next door, and had both been crestfallen when he left to go out West.

“I’m not certain, girls. I notice his mother keeps a candle in a lantern in her front window all night now,” Mrs. Bennett said, peering at Mrs. Lowe’s brick ho

use next door. The drapes were closed tightly except in the bow window, where the lantern shone brightly.

“But I met her coming back from the Custom House the other day,” Mrs. Bennett continued, twisting a piece of her dark hair behind her ear. “She was checking to see if there was any news about when ships from San Francisco are due in. Remember when Lucas was a little boy, George? Frances used to take him sledding on the Common, and she would go down the hill on the sled with him. She was the only mother who did that! And she would laugh as loudly as any of the children. I think she just set to worrying when Lucas went out West. She’ll feel sunnier when he returns.”

“Excuse me, but I need to get home now. My ma will need me to help with supper,” Mary Margaret said, carefully packing up her new doll clothes. “Wait till I show all these to Bridget.”

“How is your sister, dear?” Mrs. Bennett asked.

“Even more under the weather this past week, I’m afraid,” Mary Margaret answered. “But Ma says she thinks she sees the color coming back to her cheeks.” She left through the back door, being sure to close it tightly the way her ma had instructed her, and then hurried down the steps to the Caseys’ apartment.

The Bennetts had finished the cellar rooms in their Mt. Vernon Street house quite nicely. On the side of the house, an outside staircase led down three steps to a basement apartment where the Caseys lived. At the bottom of the stairs, a door opened directly into their tidy little kitchen with worn floors, a table and chairs, and cast-iron stove set into a hearth. The small clock the Caseys had brought with them from Ireland ticked softly on a mantel above the hearth. Two small bedrooms were off the kitchen, one for Tomas and Rose and one for their daughters, Mary Margaret and her younger sister, Bridget.

Currents

Currents