- Home

- Jane Petrlik Smolik

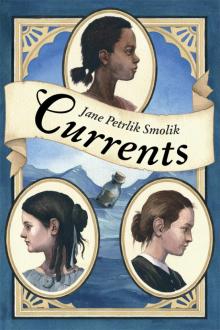

Currents Page 14

Currents Read online

Page 14

“Pay off indeed,” Louisa laughed. “Papa says if I actually get an article published in the magazine he’ll give me a silver dollar!”

“Well, now, that would be something!” Mary Margaret had never actually held a silver dollar, a fact she kept to herself.

The girls agreed that what Louisa needed was new material to write about.

Mary Margaret had decided not to tell Louisa about the bottle she and Da found. It was going to make the best story in her journal. She felt a little tinge of guilt, but it was too good to share just yet.

Chapter Forty

“And ooohh, the faerie folk. Watch out for them, Louisa.” Mary Margaret’s blue eyes grew wide. “They have been known to snatch up naughty children from their parents and leave a stranger in their place.”

Louisa was sitting at the kitchen table, listening raptly, her teacup suspended in midair. “All these stories, Mary Margaret. Leprechauns and banshees, pookas and changelings. Ireland must be a fearsome place.”

“Not if you know your way around,” Mary Margaret boasted. “And if you’re careful to watch out.”

Ma hummed softly to herself while she put the finishing touches on the Bennetts’ dinner, and Mary Margaret washed and dried the dishes and pots while regaling Louisa with her stories.

“Was Bridget asleep when you checked in on her?” Ma asked.

“No, she was reading her primer in bed,” Mary Margaret answered. “She seems a bit perkier today, Ma.”

“Let’s hope,” her mother answered. But Mary Margaret noticed Ma’s forehead was pleated with worry lines.

Ma often told her daughters that she didn’t mind cleaning and cooking in the Bennetts’ sunny kitchen with the sounds of the dishes and pots clattering, the smell of food baking or roasting. She had confided that the last few years they had lived in Ireland she woke up every day worrying how she would put food on the table. Bare cupboards. Empty potato bins. Barren fields blackened with scarcely a turnip to dice for a watery stew. They’d begun to live off wild blackberries, nettles, old cabbage leaves, edible seaweed, roots, green grass, and even roadside weeds. Mary Margaret had vague memories of that time.

After those days, Ma often told Mary Margaret and Bridget, she would never take the smell of supper cooking for granted.

“You could be the writer, Mary Margaret,” Louisa said. “The stories you tell are wonderful. And if you write them down half as well as you tell them, you should become an author, too.” Louisa drained her cup with a slurp. A drop fell on the flounce of her skirt, and she brushed it off absentmindedly.

“No, I must work for a living as soon as I’m able. But I do write in my journal a lot. Stories about my life,” Mary Margaret said. “Sometimes about the customers that come in to Mr. Eaton’s. I wrote a story about the time Lucas Lowe took you and me sledding on the Common, and that strange man asked him if I was an Irish mick, and Lucas threatened to sock him in the nose if he called me a name again!”

“Ha! Wasn’t he wonderful that day?” Louisa said. “He was so brave. Oh, Mary Margaret, won’t you let me read your journal?”

She was flattered to think that Louisa, living in this grand home, with her beautiful dresses and fancy rooms, would want to read what she wrote.

“Mary Margaret, it’s time to go,” her mother announced, placing a cloth over the still-hot bread and a cover on the beef stew she’d prepared for the Bennetts’ dinner. “Did you fill the scuttles with coal from the back?”

“Yes, Ma,” she answered.

“Well, then, pick up your wild stories and your coat and say your thank-yous for the tea and cookies.”

“Mary Margaret, I have a thought,” Louisa said. “Can you run down and get your journal now? I can begin reading it tonight, and you can come back for tea when I’m done, and we can discuss it. Oh, please? Your stories are too dear for me to wait another day.”

They both looked at Mary Margaret’s mother.

“Aye. You can run along now and fetch it,” her mother said, slipping her white apron over her head and tucking it in the wash hamper.

“Louisa,” Mrs. Bennett called down to the kitchen. “Please change for dinner.”

“Just bring it up to my bedroom,” Louisa said. Before vanishing up the staircase, she wrapped two fresh cookies in a napkin and gave them to Mary Margaret. “Here, these are for Bridget. Please tell her I’ll be glad when she feels well enough to come back upstairs with you and your mother.”

It wasn’t hard to locate her journal in their little home. The Caseys had so few possessions that everything was easy to find. Her father said that was the wonderful thing about how they lived now: no one had to hunt around through a lot of useless clutter for their belongings.

Ma said that when Da, the eternal optimist, died, she was going to have an old Chinese proverb carved on his tombstone. It would read: Now that my house has burned down, I have a better view of the mountains. He often hopefully referred to Bridget’s symptoms as growing pains, which irritated Ma to no end. “Joint pain, numbness, too weak some days to even walk?” Ma would sputter. “Tomas, I don’t know what it is—but I know what it isn’t.”

Ma brewed endless teas and herbal poultices, all recipes from the old country, that she packed on to Bridget’s swollen knees and ankles in a vain attempt to make her youngest child robust again. At times they seemed to help, but then Bridget would take another turn downward.

Out of breath from running down the stairs and back up, Mary Margaret was anxious to take another look around Louisa’s bedroom. Days when she helped her ma with chores at the Bennetts’, she often watched as Louisa rushed up the stairs after school with her friends. They all dressed alike, with long bell-shaped skirts decorated with laces and braid. Sometimes they would bring their dolls along—even they were dressed in finery such that Mary Margaret could not have dreamed of.

“It’s all right, dear. Just go on up.” Mrs. Bennett waved her toward the stairs. Mary Margaret walked her best ladylike walk past the third floor where the Bennetts’ bedroom was, making sure to keep her eyes downcast.

“Louisa?” she called out softly when she reached the top of the staircase.

“In here,” Louisa called from her room, as she finished adjusting the bow on the back of her dress. Mary Margaret placed her journal in Louisa’s hands as if it were a precious jewel.

“I swear, I will take care of the beautiful prose in your journal like you can’t imagine. You have my solemn oath on that,” Louisa vowed.

“I know you will. We’ll discuss it another day, perhaps over tea, like you said.” Mary Margaret Casey tossed her shawl around her neck with a flourish and marched back down to her home.

Chapter Forty-One

Mr. Eaton was bent over a pair of black patent-leather slippers, his balding head shining in the light, when Mary Margaret came to work early.

“Well, you are eager to get to your ironing today!” Mr. Eaton said, glancing up at the clock..

“Yes, sir,” she said. “But I was hoping you might have a minute to look at something my da and I pulled up from the docks the other day. Sure it’s a grand mystery, Mr. Eaton.”

“Well, it’s slowed down a bit here, so I don’t suppose it would do any harm. And I do love a good mystery. What is it you have there? Let’s have a look.”

She pulled the bottle from the bag where she had carefully stowed it and placed it in his hands.

“Mr. Eaton, sir, there is a note that appears to be about a slave’s birth and a splendid gold cross on a chain inside. My ma says it would fetch a pretty penny.”

“Oh, my.” He carefully shook out the note and cross before pushing his spectacles up on his nose to get a better look. He squinted and held the bottle and gold cross closer to the light.

“The bottle certainly has an unusually wide mouth on it,” he noted. Then he rubbed his finger over the bottom. “Here. Here is a marking. See this? It’s an anchor. Looks like an anchor inside a circle.” He explained to her that s

ome things could be told about bottles by their markings, and perhaps the bottle she found had such identifications. He moved his head so Mary Margaret could see for herself, and she leaned in and examined it.

“What would that stand for?” she asked.

“Let me see,” he said, rifling through a few different stacks of books. He pulled out a thin volume about glassmakers and their identifying marks from one of his tallest piles. He thumbed through carefully for several minutes until he stopped and slapped a page. “Aha! Look here!”

Together they studied a page that had a drawing of the anchor inside a circle, exactly like the one on the bottom of her bottle.

“What do you suppose it stands for?” she asked.

“Well, let’s see. It says that it is the mark on bottles that were made at the Richmond Glass Company in Richmond, Virginia. Of course, we can only speculate how or where it went into the water. The bottle could have been made in Virginia and ended up anywhere after that. That’s really all that we can know from this.”

“The cross looks to be real gold.” He rolled it over in his fingers. “DSS J. K.,” he read. “Doesn’t mean anything to me. They appear to be someone’s initials.”

Mr. Eaton examined the note that was inside the bottle. “Perhaps a slave girl on a Virginia plantation. Again, no way of really knowing, I’m afraid. You were right about one thing, Mary Margaret—it is a grand mystery, indeed!”

He carefully returned the note and necklace to the bottle and handed it back to Mary Margaret. The bell above the door tinkled and a customer entered, inquiring after her boots.

Chapter Forty-Two

The next week Mary Margaret arrived at Mr. Eaton’s shop bubbling over with curiosity about Miss Daphne Cummings. Mr. Eaton hadn’t mentioned her again, but Mary Margaret now noticed the smell of cinnamon whenever she came in to work. None of their regular customers smelled of cinnamon.

“Good morning, Mary Margaret,” Mr. Eaton said.

“Good morning, sir.” She gave him a sly smile, and he returned it.

“How is Miss Cummings, if you don’t mind my asking, sir?” she said, hoping she wasn’t being too bold.

“Well,” he began, “Miss Cummings has visited here two weeks in a row now. She’s a very fine lady. And I met her this morning for a walk by the Frog Pond. I’ll see her again this evening, as well.” He looked down at his lap and blushed. “And every evening after that she’s free and will see me.”

“And I believe she smells of cinnamon.” Mary Margaret tilted her freckled nose up.

“She does indeed.” He chuckled. “But of course, we can only see one another for a couple of hours a few times a week because of her mother. Apparently, Mrs. Cummings is terribly ill. And poor Daphne is all the family she has in the world. The dear girl is limited as to what work she can do, as she needs a cane to get around. I don’t want to be indelicate and ask her what she uses it for, but it seems she has a slight limp.”

“Ah. I understand. My sister sometimes needs a cane and it does slow her down, but she still manages quite well. Da says that sooner or later everyone has something they must learn to live with.

“Well, then,” Mary Margaret continued. “As I see it, sir, you and Miss Cummings are both practically alone in the world. So it’s a grand thing that you’ve found one another.”

“It’s true,” Mr. Eaton said. Mary Margaret hoped he wasn’t feeling embarrassed at having shared so much. “Well, now, enough of this idle chatter. If we don’t get to our work, I won’t have money to pay you or to take my new lady friend out for tea and cakes!”

Chapter Forty-Three

Mr. Eaton barely looked up when Mary Margaret reported for work again the next day. She immediately saw why. There were at least twice as many shoes and boots as usual waiting to be repaired and cleaned.

“I’ve left three dozen pair out there for you. You’ll have your work cut out for you this morning,” Mr. Eaton said. “Seems with the holidays that everyone wants to look their best.”

The scent of cinnamon lingered in the air, and she spied two empty teacups on a tray by the stairs. Looks like there’s going to be a new Mrs. Eaton, she thought gleefully as she disappeared behind the red drapes.

They each worked in silence for the next hour, knowing that at noontime, the customers would come flocking in on their lunch break looking for their footwear.

An hour and a half into their work, the bell above the front door tinkled. Mary Margaret heard a customer enter and let out a sob.

“Miss Cummings!” Mr. Eaton jumped up from his bench, wiping his hands. Mary Margaret stopped ironing and stood quietly peering out from the small opening where the curtains met.

“Oh, Mr. Eaton.” She heard the lady’s voice breaking. “I had nowhere else to go. No one else to go to. I’m sorry.”

“Sit down, sit down,” he said. “Is it your mother? Has she taken a turn?”

“No, no. It’s, it’s . . .” Daphne, looking pale and weak, leaned on a dainty white cane in one hand and clutched a handkerchief in the other.

“Tell me,” he urged. “And here, please sit down. Now, there, there. Tell me, what is it?”

“Well, Mother has needed more and more medicine to keep her comfortable in these final months,” Daphne explained between sobs.

“Of course.” Mr. Eaton patted her hands. Mary Margaret could see that she was a tiny woman, with little birdlike features and pale brown hair twisted up in a bun. A bright red hat with a jutting feather was fastened at a slight angle on top of her head. She had a pleasant if rather unremarkable face, except for very large dark brown eyes.

“And because she is bedridden, she is cold all the time. So sometimes I have purchased extra coal for the fires,” Daphne whimpered.

“Naturally.” Mr. Eaton nodded sympathetically.

“Between the medicine and the coal and the doctor’s bills . . . oh dear. I’m so ashamed. The rent is two months past due, and I do not have the money to pay the landlord. He’s threatened to throw Mother and me out on the street!”

“Daphne, Daphne. Is that all?” He sat back and visibly relaxed. “I thought there was a problem we couldn’t fix. We can take care of this.”

Mr. Eaton took a key from a chipped cup on the desk against the side wall and opened the bottom drawer. He lifted out a metal box, opened it, and pulled out a small stack of bills.

“What do you need to bring your accounts up-to-date?” he asked firmly.

“Elton, I will pay you back—I give you my word. It might take me a month or two, but you’ll get back every cent.” She swiped at her tears with her gloves, and he handed her a fresh handkerchief.

“I know you will,” Mr. Eaton said.

Mary Margaret couldn’t make out the amount Daphne asked for, since the poor woman was still weeping, but she saw Mr. Eaton peel off several bills from the stack and watched as the lady tucked them neatly in the reticule she carried.

“Dry your eyes and go take care of your obligations, my dear. I will see you tonight.” He stood up, passed her the cane, and helped her to the door.

After she left, Mr. Eaton pulled the red drape open and looked down at Mary Margaret. “I ask you,” he said, “to please not repeat what you just heard here.”

She nodded gravely. “I promise, Mr. Eaton. I won’t say a word.”

Chapter Forty-Four

Mary Margaret struggled to keep up with Louisa as she rushed down the street and up the steps of the Boston Girls’ School. Her feet had grown that fall, and her shoes pinched her toes. There was no use complaining, as she already knew there would be no money for new boots or shoes until next year. Louisa’s hands were tucked inside her fur muff to keep them warm, so Mary Margaret pulled back the brass knocker and rapped several times. The door swung open, and Mrs. Lowe stood looking down at the two of them. She was dressed in a stiff blue dress with a skirt shaped like a church bell, and the mourning broach she’d worn since her husband’s death was pinned tightly at her collar.

“Yes?” she asked.

“Mrs. Lowe,” Louisa said breathlessly, pulling a hand from her muff. She held up the letter her mother had asked her to deliver. “This letter was mistakenly delivered to our house instead of yours. Mother says it looks like it’s from California and that I was to bring it directly to you.”

The older woman’s face took on a light that Mary Margaret hadn’t expected from Mrs. Lowe. It touched her heart. Mrs. Lowe took the letter and opened the door wide.

“Come in Louisa, dear. You, too.” She nodded at Mary Margaret. “You’ll freeze out here. Hyacinth!” she called out. A young woman appeared from around the corner. “Please give the girls some tea or hot chocolate and show them around. Then deliver them to my classroom to wait for me.” She spun on her heel, carefully opening the letter as she disappeared into her office.

“Would you like to have a tour of the school?” Hyacinth asked.

“Oh, yes. I go to the Young Ladies’ School on Beacon Street, and I’ve heard of this school. A friend of mine is a student here,” Louisa explained. “She says it’s awfully hard, and she must study even on weekends. I’m not sure that would suit me.”

The blue and purple multipaned glass windows poured light like a rainbow on tall rows of bookcases that lined the walls. There were three large, sunny teaching rooms on the second floor, and Mrs. Lowe’s and Hyacinth’s offices were on the first floor. One classroom had twelve desks lined up neatly in three rows of four. The other rooms had chairs placed evenly around a long oak table. A box in the center of each table held several freshly sharpened pencils.

“Do you study needlepoint here?” Louisa asked.

“No,” Hyacinth said. “Our girls study the classics, mathematics, science, history, and some study the French language.”

Currents

Currents