- Home

- Jane Petrlik Smolik

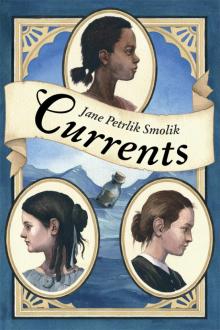

Currents Page 16

Currents Read online

Page 16

“Mary Margaret, are you hurt?” he asked.

““No, no I’m fine. I came to warn you, sir. This woman is not who she said she is.”

“So I was told,” Mr. Eaton said. “Officer Dyer came and filled me in last night. Seems I’ve been taken, but that’s all right. My pride may be even more wounded than my bank account.”

The Caseys’ little kitchen was soon crowded with the three policemen, all four of the Caseys, and Mr. Eaton.

“How could you not tell us, Mary Margaret?” Her mother fumed. “Were you out of your mind, lass?”

“I’m afraid it’s me you should be angry with, Mrs. Casey,” Mr. Eaton spoke up. “I was a little embarrassed about beginning to keep company with a lady, and I didn’t know if it would turn out in marriage or not. I didn’t want people gossiping about me. You know how people can be.”

“Ah, I do.” Ma nodded. “But still, Mary Margaret!” She shook her head and tossed up her hands.

“Well, I can assure you she is in no trouble,” Officer Dyer piped in. “We had been onto this Cummings couple for a while now. They’ve been fleecing men with their lonely-hearts swindle around Boston, and some of the gentlemen had come to us to complain. So when I saw Daphne coming and going from Mr. Eaton’s shop, I said to myself, ‘Well, here she goes again!’ And this time we pinned her and that no-good husband of hers. Your Mary Margaret just happened to be there when it all came crashing down. We had informed Mr. Eaton of it just yesterday. He told Daphne he would be out all morning, and we hoped she might come by. That’s been their usual pattern in the past. We were right. We just hadn’t planned on Mary Margaret showing up.

“And by the way, that was quite the blow ya landed on the side of his head, Mary Margaret,” Officer Dyer said, obviously impressed. “What did you hit him with, a shoe hammer?”

Mary Margaret smiled broadly. Then with great drama and flair, she slowly pulled her bottle, miraculously unharmed and with the torn page and gold cross still inside, from her bag and held it up triumphantly.

“’Tis covered in glory, it is!” Mary Margaret declared as she beamed.

Chapter Forty-Eight

Da was already home when Mary Margaret raced down the icy steps to their apartment a couple of nights later. Something wasn’t right—she could tell from the looks on her parents’ faces. Sitting across from each other at the small table, Ma kept fingering a piece of paper—smoothing it out with her index fingers and tapping it with her thumb.

“What’s that? What’s going on?” Mary Margaret unwound her scarf and stuffed it up the sleeve of her coat before hanging it on a hook by the door.

Ma didn’t say take your boots off before you come in and get dirt all over my kitchen floor the way she always did. She just continued to stare at the table and the piece of paper.

“A fella I work with,” Da began, “has a daughter with the same problems that our Bridget has. Numbness around her mouth, pain in her hips . . .”

“She knows the symptoms, Tomas, no need for you to recite them,” Ma snapped.

“They took her to this doctor. They gave me his name and address.” Da pointed at the paper in Ma’s hands. “Doctor seemed to know right away what was wrong. Gave them some medicine that she takes twice a day, every day—a month later, she’s as good as new. Almost as good as new.”

“And?” Mary Margaret went over and took the empty seat between her parents. “So why the glum faces? ’Tis wonderful news, isn’t it?”

Da dragged his fingers through his hair a couple of times and cleared his throat.

She figured out the answer in their silence. “How much does it cost to see this doctor and get the medicine?” she asked, knowing that whatever the answer was, it was going to be too much.

“Where is Bridget?” Mary Margaret then asked, lowering her voice. Ma nodded to the closed bedroom door.

“Perhaps if he met us—” Mary Margaret said hopefully, “this doctor.”

“Don’t, lass,” her mother said. “No doctor is going to see no Irishman without seeing the money first.”

Mary Margaret stood up and lifted her bottle from its place of glory on the mantel and carefully shook out the gold cross. “Mr. Hamilton’s pawnshop is right next to Mr. Eaton’s shoe store. Ma, you said yourself it would fetch a pretty penny.”

“Aye, it might,” her ma said, brightening a bit. “I was thinking about selling the clock we brought with us from Ireland.”

“There’s no need to do that, Ma. The clock was your ma’s. I don’t need the cross anymore. I wondered why I’d found it, and now I know.”

“I’ll take it down tomorrow and see what the fellow at the pawnshop says,” Da added.

“I’ll go with you, Da, on my way to work. Mr. Eaton has asked me to come in the morning. I can introduce you to Mr. Hamilton. He seems nice enough.”

“Get washed up, then.” Ma stood up, indicating that the matter was settled. “And see if Bridget feels well enough to come out for supper.”

Da reached over and wrapped Mary Margaret in his arms, kissed the top of her head, and rocked her a little. “So you see how funny a thing fate is, Mary Margaret? It may turn out that you finding that bottle was indeed meant to be. Ah, lass,” he said tenderly, “you have a beautiful heart. That’s not something you can put in a child. You were born with it, sure as rain.”

Mary Margaret was surprised when she left work the next evening to see the gold cross prominently displayed in Mr. Hamilton’s pawnshop window. She had thought it would be gone right after Da brought it down, snatched up within a few hours of being displayed. Mr. Hamilton saw her standing outside and leaned out his front door.

“It won’t be here long. Someone will see how lovely it is.” He smiled before closing the door against the bitter cold.

Chapter Forty-Nine

Mrs. Bennett gave Ma the morning off to take Bridget to the doctor. Ma, Bridget, and Mary Margaret were the first ones to arrive at his office and the last patients he saw before lunch.

“We were here first,” Mary Margaret whispered to her mother when one patient after another was seen ahead of them.

“Hush, you’ll get us thrown out,” Ma whispered back. “We’re lucky he agreed to see us at all. As it is, we had to pay up front.”

“Ah. Ah,” the doctor uttered when he finally examined Bridget. Ma carefully explained all her daughter’s symptoms while he poked and prodded and peered into her ears and eyes and down her throat.

“Well, I think I can help you,” he pronounced. “I’m not promising anything, but it looks like a kidney issue that I have seen before.”

Ma couldn’t help it—she let out a gasp of relief. Embarrassed, her hand flew up to cover her mouth.

“We aren’t sure exactly why, but these symptoms seem to indicate a problem with her kidneys not working properly. Leaves too much acid in the blood,” he explained.

“If I’m correct, the child needs to take sodium bicarbonate or potassium citrate to correct it. I’ve seen cases like hers clear up in as little as a month. She’s had it untreated for so long that she may have a few lasting complications. She might not grow as tall as she would have otherwise—but nothing that would stop her from leading a normal life.”

“That’s all?” Mary Margaret asked, incredulous.

“Count your blessings that some problems are easily solved. I’m quite sure this is one of them,” the doctor said firmly, scowling at her.

As an afterthought he asked, “I don’t suppose either of you have read A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens? Do you know how to read?”

Highly insulted, Mary Margaret spoke up, “We do indeed, doctor. And I have certainly read and enjoyed Mr. Dickens’s A Christmas Carol.”

“I see,” he said, a little surprised. “Well, then, you’ll remember Tiny Tim and his ailments. A lot of doctors, me included, think that the character of Tiny Tim had a renal disease. That’s what I think young Bridget here has. Looks awfully bad and is indeed if untreated. But it

’s one of those conditions that can be fairly easily addressed. Too bad you didn’t bring her in to see me sooner. She might always have a lingering limp. Hard to say, exactly.”

They left the doctor and headed directly to the prescription pharmacy on Charles Street. They passed Mr. Eaton’s Shoe Shop, and Mary Margaret waved. At Mr. Hamilton’s window she felt her heart fall a little when she saw that the gold cross was gone, even though she knew the money was important to her family, especially Bridget. She hoped that whoever bought it would think it was as special as she did.

“Ma, may I go in and see Mr. Hamilton while you get the medicine?” The pharmacy was down only three doors, and Ma was in such fine spirits that she would agree to anything.

“Good afternoon, Mr. Hamilton,” Mary Margaret called out, carefully closely the door behind her.

“Ah, I’m guessing you noticed your cross is gone? Yes. Fellow came in just before I closed last night. Never saw anyone so excited. Held it for the longest time, turning it over and over and saying he couldn’t believe it. I think he wanted it for his mother. Gave me half the price then and there and is coming back this afternoon with the rest,” he said, pulling the cross out from a drawer. “I’m keeping it here until he comes back.”

“Was he a fancy gentleman?” Mary Margaret asked. She imagined her cross hanging from the neck of one of the society women who lived on Beacon Hill.

“No. No, in fact he looked to be a common man. A little scruffy, truth be told. Said he works the docks some days. Sounds like he takes whatever work he can get. But his money’s as good as anyone else’s.”

He hesitated for a minute before he spoke very kindly. “I’m sorry you had to sell it, Mary Margaret. I can tell it means a great deal to you.”

“I’m content with it, Mr. Hamilton,” she said. “It’s served its purpose. It was good for something, while it was in its power.”

He cocked his head to the side. “Where have I heard that before?”

“Marcus Aurelius, sir,” she said. “He said we shouldn’t live as if we had ten thousand years, but we should be good for something now, while it was in our power.”

“Yes, that’s right. It’s been a while since I’ve heard it. It’s a fine way to look at life.”

He put the cross back in the drawer when the bell over his door tinkled and a customer entered.

Mary Margaret left quietly when Mr. Hamilton approached the new customer, and she rushed up Charles Street to catch up with Ma and Bridget.

Chapter Fifty

The weather had held up until most Bostonians were home from Christmas Eve church services, but soon after dark, a soft snow began to fall and cover the city in a silvery blanket.

“Ah, here they are,” Mr. Bennett said as he threw open the front door, thrusting his hand out to Tomas Casey and his family, who stamped their shoes in the vestibule before entering. Da carried Bridget on his shoulders, and she hung on to him with her arms wrapped around his neck.

“Easy, Bridget,” he said, “you’re near choking your poor old da.”

“Oh, my!” Mary Margaret sang out when she saw the tree with lots of candles lighting it up. “’Tis the most beautiful tree I have ever seen.”

The Bennetts’ tree was splendid, dripping with hard candies and trinkets, its branches aglow with little white candles. The fireplace sizzled and snapped with the sea coal Mary Margaret had carried in earlier in the day.

“Oh, Mary Margaret,” Bridget exclaimed, feeling a little superior from her high perch, “you’ve never seen any Christmas tree before!”

“Merry Christmas, Louisa.” Mary Margaret smiled at her friend. Louisa was dressed in a long, black velvet dress with a cream-colored ribbon at her waist, to match the one tying up her dark curls.

“Merry Christmas to you,” Louisa replied, not quite looking Mary Margaret in the eye. Instead she scooped up Boots and buried her face in the cat’s silky black fur.

“Merry Christmas to you, sir,” Da said, pulling off his cap. “And to you as well, ma’am.” He nodded politely to Mrs. Bennett. They stood awkwardly for a moment in the front hall, not sure if they had been invited to make a brief appearance at their employers’ home, or if they should come in. Mrs. Bennett put an arm around Mary Margaret and steered her to the glowing tree.

“Come right in for a minute.” Mr. Bennett waved toward the tree-lit parlor. Mary Margaret noticed that Da didn’t take a seat, but stood with his family respectfully at attention. “My goodness, what a week your family has had, Tomas! Rose told us all about the trouble at poor Elton Eaton’s shop—and little Mary Margaret being caught up in the middle of it. Thank heavens they caught the scoundrels, and especially that Mary Margaret is fine. You’re a heroine, young lady!” Mr. Bennett beamed at her.

This is going to be a lovely Christmas, Mary Margaret thought.

The dining room was directly across the hall from the parlor, and Mary Margaret noticed her mother glance in, admiring the work they’d done together earlier that day. Mary Margaret had polished the buffet serving tables and all the chairs that morning with lemon oil. The long, oval dining table was covered with a freshly washed and pressed damask cloth. She had rubbed the silver candelabras until she could see her reflection, and then Ma had placed them in the middle of the table with candles ready to be lit for the Bennetts’ Christmas Eve dinner of goose and plum pudding.

Mrs. Bennett reached up to the tree, pearl earbobs the shape of teardrops fluttering from her ears. “Well, look what I found. A little something for Mary Margaret and another for Bridget.”

She placed a bundle of four pencils and a lined notebook in Mary Margaret’s hand and a soft blue scarf in Bridget’s, each tied with a long red ribbon.

Ma nudged her daughters and they responded politely, saying, “Thank you, ma’am.”

“Well, don’t untie them now. Save them for your own celebration,” said Mrs. Bennett. “We just wanted to give you a little something for the good service you have given us. We’re happy you’re with us.”

“How lovely your tree is, ma’am,” Ma said. “All the ornaments and wee candles. Sure, it’s magical.”

“Thank you, dear,” Mrs. Bennett said. “Some of them we’ve had for many years. Some are brand-new. This is the first year we’ve had a tree to show them off, though. George finally consented. After all, if the President of the United States can have a Christmas tree in the White House, the Bennetts can have one in Boston.

“We’re particularly proud of the newest decoration for our tree.” She plucked a silver dollar off a branch and held it out for the Caseys to see. “Our Louisa has finally had a piece accepted in Merry’s Museum Magazine.”

Louisa shrank farther back into the room, almost disappearing into the potted plants and flocked wallpaper.

“Now, now, come up here, Louisa.” Mr. Bennett waved his beefy hand toward her. “Don’t be shy. I bet Mary Margaret will be pleased to see she and Lucas Lowe are both part of the story. The publisher sent us an advance copy since Louisa had an article printed. Gosh!” He beamed. “I think it’s awfully good.”

He picked up the copy of the latest edition of Merry’s Museum Magazine and pointed to the story.

THE RED SLED

by Louisa Bennett

Mary Margaret edged up to the magazine and blinked hard when she read the title. The first sentence was as familiar as the back of her own hand, and she quickly skimmed over the page. She couldn’t believe her eyes. Her words, her story, word-for-word from her journal, but with Louisa Bennett listed as the author. Her parents read the first few lines at the same time, both quickly recognizing Mary Margaret’s story.

“Well, you should be proud indeed,” Da said, passing the magazine back to Mr. Bennett.

Mary Margaret stared at Louisa.

“How could you?” she barely whispered.

“What’s that you say?” Mr. Bennett asked.

“Aw, she’s just impressed with your daughter’s clever writing.” Da clenched Mary

Margaret’s arm.

“And Rose and I, we want to thank you for your kindness and your gifts. I know the girls will enjoy them. We won’t be taking up any more of your time tonight. We’ll be going back downstairs. Come on, girls. Rose.” Mary Margaret glared at Louisa, ignoring her mother’s fierce stare and Da’s viselike grip.

Mary Margaret barely heard the large front door with the lion’s-head knocker shut behind them, nor felt her feet on the icy walk. It wasn’t until they reached their rooms down the little side steps that she burst into tears.

“That beast. She’s a beast!” she howled, throwing her bundle of pencils on the floor. “And I want my journal back—now I know why she’s had it so long!”

Ma quickly retrieved the pencils. She knew Mary Margaret would need them, and there was no money in the Casey budget for pencils. What the Caseys could not bear was to be tossed out in the street over a story in a magazine.

“We have a roof over our heads, Mary Margaret. Look around you, girl.” Her mother’s voice was stern. “The Irish are sleeping in sheds and alleys and abandoned buildings. You’ll say nothing about this to Louisa.”

Mary Margaret nodded but pulled up her scarf and stomped back outside in the icy cold night to sulk on the stoop. Her father followed her, stopping the door from slamming.

“Is this seat taken, Mary Margaret?” Da stood over his older daughter as she sat shivering in the cold, and draped her coat over her thin shoulders.

“She stole it from me, Da! She stole my story about Lucas and me. How could she? Why didn’t you let me say something?”

“You know why,” he spoke firmly. “We need this home and this work. The Bennetts are good folks. You must understand, Mary Margaret, if they decide they don’t want us anymore, we have nowhere to go.

“Look, she only took from you the words, lassie. She cannot really steal your story. It is yours. No one can take it away from you. And no one can steal your talent either. It is God-given, sure it is.”

Currents

Currents