- Home

- Jane Petrlik Smolik

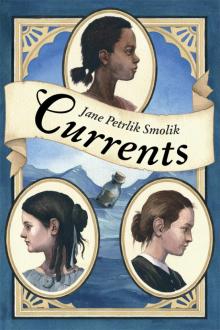

Currents Page 5

Currents Read online

Page 5

Agnes May Brewster

Born: July 1843. Colored slave.

That was all. She closed the book and furiously dusted and waxed around the room a second time, always keeping her ears open. Finally, she picked up the little red book again and quickly found her page. Her fingers trembled as she slowly, quietly, and inch-by-inch tore the page away from the spine, folded it in half, and tucked it deep inside her apron pocket. She placed the book back where it belonged and walked quickly out the back door and down the path to the kitchen house, her heart hammering in her ears.

“You finally done, Bones?” Queenie asked as the girl neatly replaced the linseed oil and dusting rags in the kitchen’s cleaning cupboard.

“Yes’m. I’m goin’ home now for a minute before I go back down to the fields. Don’ feel so good. Linseed-oil vapors got to my head.” She shoved her hands in her pockets so Queenie wouldn’t notice them trembling.

She ran back to the cabin and took the bottle that held her carved heart out from under the sleeping pallet. She read the page with her name one more time, then quickly rolled it up, stuffed it inside the bottle alongside the carved heart, and corked it. She took a candle from beside the fireplace, lit it, and held it over the cork, letting the wax drip down and seal the stopper around the bottle’s neck. Outside, she looked around to be certain she wasn’t being watched and crawled underneath the cabin to hide the bottle next to a rock.

The danger of her impetuous act weighed on her more and more as the day went on. Granny and Mama were still working in the fields when she got back to the cabin that evening.

That night it rained hard, the drops making pingping sounds as they found their way through a small hole in the roof and hit the metal pot that Granny kept by the door. Thank goodness I sealed the top of the bottle with wax, Bones thought. What if the rain started a river of mud that ran under the cabin and flushed the bottle out from behind the rock and into the open where someone might find it in the morning? What if some animals drug it out? Bones lay in her space on the straw pallet between the two older women, her mind racing with unruly thoughts of the punishment that was sure to come if her crime were discovered. And this time she knew she would not be alone in the punishment. It was unbearable to think what Old Mistress would do to Granny and Mama.

“Why you so jittery? You thrashin’ so much I can’t sleep,” Granny complained, punching down the straw under her head into a more comfortable shape.

“I’m not,” she protested, faking weariness and squeezing her eyes shut. Where could she move the bottle so it would be safe? She considered the woods. But the forests in these parts were infested with panthers and bears, and she had seen bears walking like a man out of Master’s fields, carrying ears of corn in their arms. The only time anyone went into the woods, they were on horseback or armed with axes to chop down trees for firewood. For every spot she thought of, she could imagine the Wolf Woman sneaking up on her like a whisper, discovering her, and the whupping and salty vinegar that would follow. She had been warned, and next time it would be worse. She might even be sold. Taken away from her Mama. She wondered if her pappy knew when they called him and the other men up to the big house that they were going to sell him that day or if he thought it was a day like any other. Did he think he was going up to trim Old Mistress’s hedges or paint the front door? Did he wonder when they shackled him to the other two slaves and threw him in the back of the wagon how his wife would feel?

Bones would rather die than be sold. Agnes May would rather die.

Chapter Thirteen

The next morning, Bones awoke to the sound of the turkeys plopping down from the trees. She quickly slid out of bed and out the door, and walked around the cabin. There was no bottle lying on the ground in the open. She blew out a deep breath and went back inside.

“You walkin’ in your sleep, Bones?” Mama asked, rubbing her own eyes. “What were you doing?”

Bones let out a quick laugh and lied. “No, I’m not walkin’ in my sleep. I just thought I heard Queenie comin’ with breakfast.”

“I told you the Lawd gave you those big ears so you could hear extra good!” Granny said, gleefully. “Listen now. You hear that? That’s Queenie’s wagon coming now. Bones heard it before anyone else.”

The roosters carefully picked their way across the dirt yard, stopping occasionally to crow and yank an unlucky worm from its hiding spot in the damp ground. Doors creaked up and down the rows of slave quarters as people came out for breakfast, carrying their mussel-shell scoops. Queenie’s horse-drawn wagon rattled down the muddy road carrying the big pots filled with corn bread porridge and molasses laced with whatever meat was left over from the Brewsters’ dinner the night before. She stood and scooped heaping servings onto each wooden tray, her beefy black arms still coated with a dusting of fine white flour from the biscuits she’d made earlier for Master’s breakfast.

A half hour later, the trays were returned to the wagon, and Queenie prepared to drive back to the kitchen. The slaves headed off to the morning’s work, and the sun began to rise up over the river.

“Bones, Masta wants you to carry water to the field hands again today,” Queenie said. “They be workin’ extra to get in the harvest. Need every hand they can get in the field.” She stared down at the child, her chin rolls bunching up like an accordion. The cook hoisted her broad hips up onto the wagon’s seat with a groan. She practically blotted out the sun as she waved for the little girl to follow her back to the kitchen house to clean the breakfast dishes and start preparing for lunch.

“You can brings that little corncob baby doll with you. Too bad she can’t carry water, too.” Queenie laughed at her little joke.

Bones nodded, chasing behind the wagon up to the pump house to fetch the water gourds. Just outside the kitchen door, Master’s dogs lazed by the back steps, waiting to be called to run with the horses. They ate the same meals as the slaves, only the dogs were served first. Bones wrapped the strap around the back of her neck and the two gourds hung down on either side of her chest. She headed down to the river to begin her water brigade, which would go on all day again today: Fill the gourds, go to the fields. When a man or woman raised their hand, she would rush to give them water. When the gourds were almost empty, she would head back down to the riverbank to refill them.

The safest place to collect water from the James River was a small finger of land dotted with scrub pine and dwarf oak that dangled out into the river just below the fields. Currents swirled in a shallow pool on the inside crook of the finger, so a person could easily catch the water here without slipping into the faster-moving river and risk being carried downstream.

Bones’s body was in the fields that day, but her mind was drained of all thoughts save for the bottle hidden under the cabin. There was only one name on that page in the bottle—AGNES MAY BREWSTER. There would be no mistaking who had torn it from its place. And she could not bring herself to destroy it. She was someone. It said so on that paper. She was more than just someone’s little old belonging. She would have to get it off the plantation. As she crouched down, filling the gourds with the cool river water, she hatched her plan.

The dinner bell rang that evening, long after the sun had gone down. Some of the men were still straggling back from the fields, their shirts drenched in sweat, as Queenie’s wagon rattled up with huge pots of dinner. The smell of salt meat, cabbage, potatoes, and shortbread drifted above her creaky wagon. Pulling her mussel shell out of its place in her cabin, Bones was the first in line.

“Well, well. You must be hungry from runnin’ back and forth between the river and the fields. Lots harder than fannin’ flies away from Miss Liza,” Queenie teased.

Bones ignored her. She ate the scoop of food and returned the wooden tray to the wagon.

“Don’ be actin’ like you can’t hear me. With them big ole flappy ears the Lawd gave you, I knows you hears everything.” Queenie clucked her tongue. “Get a good night sleep. Need you to carry water again to

morrow, Bones.”

“It’s AGNES,” the little girl shot back.

“What you say?” Looking down, Queenie laughed at the little girl’s fierceness.

“I said, it’s Agnes. My name is AGNES!” Bones was practically shouting.

Queenie laughed like this declaration was the funniest thing she had heard all week, rolled her eyes, and sniffed. “Well, yes’m. If that’s what you say.”

“Agnes May,” said Bones hotly under her breath. “I am Agnes May. I am a someone.”

Chapter Fourteen

Thankfully the wild turkeys were as tired as everyone else that night, and they stopped gobbling early. Lying between Mama and Granny, Bones listened until she was sure Granny’s snoring and Mama’s gentle seesaw breathing meant they were fast asleep. She needed to be sure. She had been too nervous to chew her supper well, and now it stuck in her chest like a stone.

She took Lovely, with her black button eyes gleaming, off her neck and left the doll tucked safely between Mama and Granny. She slipped off the sleeping pallet from the end so as not to wake the women, and peered out the door, looking up the row of slaves’ quarters. She was grateful tonight that theirs was the last cabin, closest to the fields and the river. The primitive door sagged against the floor when opened wide, so she took care to open it only partially, and she squeezed out the narrow opening. Barefoot, she tiptoed around back and crawled, snakelike, under the cabin. She moved slowly, crouching, with her hands in front of her, feeling along. In the blackness of the night, her fingers finally wrapped around the neck of the bottle. She sucked in her breath.

The moon was growing bigger every night now. Soon it would be a full harvest moon, but tonight it showed only half of itself behind shifting clouds in the inky stillness. She didn’t dare run at full speed for fear that she would fall and the bottle would break. With light, sure steps, Bones hurried down the path alongside the now-quiet fields, past a pile of peach-tree wood waiting to be stacked the next day. She hesitated. For an instant, she thought she saw something move by the woodpile, and she strained her eyes. Nothing. She tried to keep her mind off the eerie night noises coming from the forest. A bear would be nothing compared to Old Mistress Polly if she were caught. A lantern glowed on the back porch of the big house like it did every night. It helped to keep prowling animals away. No one in the big house was awake as she slouched along, undetected under the big sky. If someone were restless and awoke and stepped onto the porch and saw her out in the middle of the night, there would be no explaining.

Reaching the edge of the river, Bones crouched down and crept out onto the same finger of land where she had gathered up water for the field slaves earlier in the day. The moon shot glittery streaks, radiating along the surface of the James River. She remembered the map of Virginia on Liza’s wall and imagined the river’s cool, deep waters rolling along for miles before emptying into the Chesapeake Bay and then pouring out into the Atlantic Ocean. It seemed to her a fine place to set her name free. She allowed herself a long moment to imagine where it might go. Her name and her heart. If only she could squeeze herself and her Mama and Granny into the bottle—they could all float away. They can own me and beat me and sell me, but a part of me will forever be free, she thought, the thrill of the idea racing through her. I’ll live forever knowing that.

Kneeling low to the water, she carefully tossed the bottle out into the stronger currents where it was immediately picked up. It bobbed for a moment before being swallowed up in the blackness, rushing away under the moon to begin its magical journey.

LADY BESS

Beginning in the Blue Ridge Mountains, the James River flows east past a series of rapids and waterfalls until it passes Virginia’s capital, Richmond. If the bottle had entered along that part of the river, it would have been less likely to survive. But the plantations were built farther east, on the Lower James, where the waters were calmer. So the bottle traveled under the moonlight, past tall trees where bald eagles roosted, down the historic waterway—the James was the first American river to be named by the colonists.

Reaching the river’s mouth, the bottle passed into the southern portion of Chesapeake Bay, which had been the gateway for the first black slaves brought from Africa. Bones’s great-grandpappy, a king in his African homeland, had arrived here in shackles to be sold in the Baltimore slave yards.

In the chop waters where the Chesapeake weaves into the Atlantic Ocean, the bottle was swallowed up by the Gulf Stream current and sped along the underwater highway across the sea.

Chapter Fifteen

ISLE OF WIGHT, ENGLAND, AUGUST 1855

Thursday afternoons are definitely the best part of my week, Lady Bess Kent thought as she picked her way through the sunflowers, lavender, bluebells, and cowslips trailing along the hillside that led down to the dock. The oldest of the fishing boats moored on the northern tip of the Isle of Wight was the Land’s End, which belonged to Chap Harris. Short in stature and bow-legged, Chap’s dark skin contrasted starkly with his crown of unkempt, silver curls and one crystal-blue eye. The other one had been lost in a fight with a pirate or when Chap was stabbed by a jealous girlfriend or in a hand-to-fin battle with a man-eating sea monster. Bess knew the story changed often, and depended on whether or not Chap had consumed a pint of ale with his lunch at The Song of the Sea Tavern. But what she was most curious to know about were the scars that ran around his neck and circled one wrist. The rough marks were much lighter than his skin, and they puckered where the wounds had obviously been left to heal on their own. She wanted to ask him how they came to be, but he acted as though they didn’t exist.

It made him all the more interesting to Lady Bess. “What does your father the duke think of you keepin’ company with an old salt like me?” he had asked her once.

“Chap, he thinks I’m at the library,” she’d answered, laughing.

“You shouldn’t be telling tall tales to your father,” Chap had admonished.

“Oh, I’m not.” She had held up a bundle of books neatly tied together. “I go to the library every week. I just haven’t mentioned that I stop here on my way home.”

The old man’s tales of his exploits and foreign travels were spellbinding, and Bess found them far more entertaining than learning needlepoint or how to properly pour tea.

“There is no doubt that I will be an explorer like my father when I grow up,” Bess announced confidently on this Thursday. “And there is still a good bit of this earth left to explore. I just hope that people don’t get to it all before I’m old enough to discover some places on my own. I’m only twelve years old, so I’m afraid I still have to wait a few more years till I can begin my explorations.”

“Ah, yes, that’s so,” Chap nodded. One of the qualities Bess most appreciated in him was that he took her at her word. “I don’t doubt you, but you live in such a grand house. And exploring is a hard life, Bess.”

“Hmm.” She frowned. “Grand, yes, but not awfully happy, I’m afraid, in the years since my mother passed away.”

“I’m sorry for that,” he said, then returned to the first subject. “If it’s an explorer you’re aiming to be when you’re grown, I can teach you some things that will be useful. For instance, do you know how to tie a ship’s knot?”

“No. I’ve asked my father to teach me when we’ve gone sailing, but he said ladies don’t need to know such things.”

“Well,” Chap said as he winked at her, “Lady explorers are a whole different matter. There are six ways to tie a proper knot on a boat. I’ll teach you the next time you come. I pride myself that there’s no man alive who can tie a finer knot than Chap Harris. And another time I’ll show you how to navigate by using only the stars above.”

“Now that would be extremely useful to me,” she said.

“Well,” he went on, “there are a lot of things I can teach you in the weeks ahead. At least while I’m still here on the island.”

“Oh no. Are you thinking of leaving?” Bess asked.

>

“No. But I’m not planning on staying either,” he said, laughing. “I get up each day and do as my spirit moves me.”

“Where were you born, Chap?”

“In America. New York,” he answered. “But I never want to go back there.”

She wanted to ask him why, but he turned away, clearly signaling he was finished with the conversation.

Bent over his work, Chap filleted the fish he’d caught that morning, tossing them into one of four large red buckets. Bess knew that he toted the fish up the hill to Parkhurst Prison every afternoon and left them in the kitchen where the cook would make a watery stew for the inmates unfortunate enough to find themselves guests of the infamous island prison. Once a month, she saw a large ship arrive at the dock, and a few dozen prisoners, shackled to each other by their wrists and waists, would board. They were shipped to Portsmouth and then to trial in London or thousands of miles away to Australia’s penal colony. She’d heard that no one ever came back. It was rumored that hard labor and disease killed at least half of them.

Finished with filling the buckets, Chap hoisted them off the boat.

“I’ll help,” Bess said as she picked up the two smaller pails and followed him up the dirt path to the backside of the large, rambling gray prison. The path to the back door was well worn and only about a hundred yards from the dock. There were guards and high wires at the front, but not at the back where the cook and cook’s help entered.

“How long have you been doing this, Chap?” Bess asked.

“Too long,” he answered.

“Then why don’t you go somewhere else?”

“I don’t really know,” he answered. “I don’t have any family. Don’t own anything except the boat I live on, and she’s in need of some repair. Got nothing holding me anywhere, so I might just as well be here.”

Currents

Currents