- Home

- Jane Petrlik Smolik

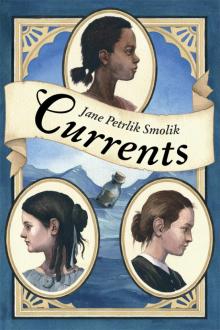

Currents Page 6

Currents Read online

Page 6

He pulled a large key from his belt, slipped it into the rusty hole, and the heavy metal door creaked open. The dark hallway was lit by one flickering gas lantern, and it took a few seconds for their eyes to adjust to the darkness. They winced as a dank, foul stench hit their nostrils.

“Poor souls,” Bess whispered, cringing. “Who could have an appetite for food when the smell is so dreadful in here?”

The kitchen was a short walk down a hallway, and they left the buckets and turned to leave. But the sound of soft crying behind another door at the back of the room stopped them, and they each pressed an ear to the door.

“It’s the room where they keep the boys who’ve been newly incarcerated,” Chap whispered. “Keep them in quarantine from the rest of the population till the guards know they haven’t got anything contagious.”

“It’s not locked,” Bess noted. There was only a small sliding latch on the kitchen side of the door that prevented it from opening.

“No, but they’re not going anywhere,” Chap said. “Must be some poor young fella cryin’ for his mum. Come on, we’re not supposed to be pokin’ around, and I’m sure I’m not supposed to be bringing you in with me.”

He locked the door behind them and reattached the key to his belt.

She picked up her stack of books from his boat and headed back down the lane to Attwood Manor with the sound of the boy’s weeping heavy in her heart.

Chapter Sixteen

With her books slung over her back, Bess ran most of the way home. When she walked in the front door she heard Mildred, the downstairs maid, muttering to herself in the duke’s study. Bess chuckled. She knew exactly what the maid was fretting about. A monstrous stuffed tiger, a full two meters high, was posed rearing on its hind legs glaring hungrily at everyone who entered the study. The beast had had the nerve to try to eat the Duke of Kent when he was on expedition in India. The duke had been gone for months, riding elephants through swamps and jungles, when one day the creature leaped out from the tall grass and ran straight at him. He had taken aim and killed the lunging cat with one shot. He had the tiger stuffed and shipped back to the Isle of Wight. The poor maids who had to dust the striped coat and polish the sharp teeth and fearsome, yellow marble eyes had nightmares ever afterward. It took every bit of willpower Bess possessed not to sneak up behind Mildred and let out a loud, howling roar. The last time she had done that, Mrs. Dow, the housekeeper, had sent her to her room with no dessert. Mildred had just recently begun speaking to her again, and Bess didn’t want to jeopardize that. Attwood could be a large, lonely house, and she needed all the company she could get. Even from timid Mildred.

“You do know he won’t bite you, Mildred,” Bess announced pleasantly, plunking her books down on her father’s desk. “He’s quite dead.”

“Oh, yes, my Lady, I know that is so. But at night—in my dreams. That’s a different matter.”

“Well, I personally intend to go to India one day,” Bess announced. “I’d like to see one of these beasts for myself.”

Mildred just shook her head. “That’s one trip I won’t be accompanying you on.”

When she heard Lady Elsie’s footsteps coming down the back stairs, the maid bent down to look busy with her chores, lest the lady of the house think she was lolling about and punish her yet again.

There was no end to the chores at Attwood Manor. There were two hundred windows to clean and a stone entrance hall hung with dozens of portraits of the Kent ancestors to dust. The rambling old estate was kept warm by twenty fireplaces that needed to be fed nine months of the year to keep out the dampness that rolled off the English Channel. The great estate sprawled across fifty acres and had been in the Kent family since the 1700s. The beautiful island was so desirable a location that England’s reigning monarch, Queen Victoria, and her husband, Prince Albert, had recently built the grand Osborne House as a retreat from the city.

Elsie, the Duchess of Kent, cleared her throat just in case her stepdaughter and the maid hadn’t noticed her looming in the doorway. She would have been hard to miss. She was nearly six feet tall in her stocking feet, though she was rarely seen shoeless.

Bess and her younger sister, Sarah, were fond of calling her Elsie the Shrew behind her back. She was scrawny as a nail and she claimed that rich sauces and sweets upset her stomach. Under her orders, the menu at Attwood had become bland and boring.

“Father’s longhorn cattle enjoy a more tantalizing menu than we’re served,” Sarah often complained. Their father was away in London on business so often that he barely noticed what was placed in front of him when he did dine at home.

“What books have you chosen from the library this week?” Elsie ran a long finger over the string that tied the books together. “My, my, you are ambitious. Five books this week.”

“One is on polar exploration, though I don’t intend to go there,” Bess explained.

“Hmmm.” Elsie purred like a sly cat. “Too chilly.”

“And another one is about New Guinea. That looks like it would be a paradise if you could avoid the man-eating tribes. The one I’m most anxious to start is about the River Nile in Africa.”

“Oh, your father and his constant going on about that Nile River!” Elsie rolled her eyes.

“He has the heart of an explorer,” Bess defended. “As do I!”

Bess held up a magazine, saying, “And this is my favorite of all. Last month’s issue of Merry’s Museum Magazine. If you want to learn about the Nile River . . .”

“I do not.” Elsie sniffed.

“Well, if you wish to learn about almost anything in the world,” Bess countered, “it will eventually be written up and explained in Merry’s Museum Magazine.”

Elsie squinted at the cover. “Is that an old man sitting on a stool?”

“Yes,” Bess said. “Poor Uncle Merry is in bad health due to rheumatism. But he has traveled the entire world, and every month he shares his stories with children. There are puzzles and songs and pictures and poems, as well. It is all very useful to someone like me who intends to explore the world when I’m old enough.”

“Yes, yes, lovely. Well, I might suggest on your next visit to the library you choose a book on keeping house or gardening. Something a lady might be interested in. Goodness, Bess, look at yourself. Your hair is a mess.”

“I’ve just run all the way home from the library,” Bess explained, trying to pat down her long black hair. “Hmmm,” the duchess murmured. “Your hair always seems to be a mess and you cannot sew or cook and in the garden—well, I’m afraid you don’t know a tea rose from a dandelion.”

She picked up Bess’s hands in her own and said, “Nails nibbled down to stubby little nubs. Tsk, tsk. You need to start acting and grooming like a lady. You are twelve years old.”

“I’m sorry, but I seem to bite them when I’m excited, and there just seems to be so much to be excited about in the world. Honestly, I don’t understand how some girls accomplish it. Getting all prettied up. And to be perfectly truthful, it just doesn’t interest me at all. I find it all to be deadly boring.”

“You need to develop an interest in it, Bess.” Her stepmother’s brow arched, and she waved a hand at Mildred, who was madly dusting and waxing in front of the drapes. “It’s unacceptable when the maid looks more polished than a lady in the house.”

Bess cringed, unable to bring herself to look at Mildred. Now she just wanted the conversation to be over quickly before Elsie inflicted any more verbal damage on the poor maid. She nodded. “I will begin putting my best foot forward.”

“Well, I do hope you will try.” The duchess shook her head slowly back and forth to show her weariness with it all. “Dinner will be ready in an hour, so I’ll see you then. And Mildred?”

Elsie pulled aside one of the heavy damask drapes. “Don’t forget to dust behind the drapes as well as in front, will you?”

“Yes, Your Grace,” Mildred replied, although the duchess was already halfway out the door.

Chapter Seventeen

The day after her weekly visit to Chap’s boat, Bess and Sarah finished their lessons with their tutors early. Bess asked Gertrude, the cook, to pack them up a small bag with biscuits and a container of sweet, milky tea so that they could have a snack when they reached Singing Beach. Mrs. Dow looked over the snack and made sure to put extra cookies in the bag.

“Remember to be especially careful around the cliffs,” she instructed. Ida Dow had been hired by their late mother to be Attwood’s housekeeper, but she had turned out to be much more. With her kind heart and unrelenting tolerance of Elsie, she had become the closest person to the girls since they lost their mother.

After a light lunch in the kitchen, Bess and Sarah set out with their dog, Sunny Girl, leading the way.

With the stone house behind them, the sisters walked through the rolling fields, past the apple orchards laden with fruit, and along the narrow paths that led down the cliffs to the ocean. Grapevines plump with fruit tangled through the bushes and stone walls, and birds swarmed them hungrily. Their father taught the girls that ripe grapes were a sure sign that summer was ending.

In less than ten minutes the smell of salty ocean air got stronger, and they could hear a squadron of gulls signaling to each other above the waves.

Cliffs rose up on either side of the narrow beach and sheltered a small cove. Ever since they were small, Bess and Sarah had been warned not to climb the cliffs or play at the foot of the rocky jetties. The English Channel’s currents sometimes sent in rogue waves that could carry unsuspecting beachcombers out to sea. Resting the picnic basket down next to a rock, the girls set out to hunt for unusual shells.

“Don’t put them in your skirt, Sarah,” Bess ordered. “The maids will never get the smell out. Use the bag that Gertrude gave you.”

Hunched over their work, they combed through seaweed and broken shells and were occasionally rewarded with a delicately sculpted winkle or whelk. They had to keep a constant eye on Sunny Girl, because she was more interested in the snack bag and the biscuits it contained than sea glass, driftwood, and shiny limpet shells.

“Sunny Girl!” Bess called out. “Come. Come here!” She whistled her best low whistle that her father had taught her, and the dog turned and bounded back across the sand.

But she stopped short before reaching the girls and began digging at something shiny poking out of the sand.

“What is it now?” Annoyed, Bess rushed up to where the dog was pawing, certain that it would be some dead, smelly animal.

Sticking up from the sand was the top of a half-buried bottle. After ordering the dog back, Bess grasped the sand-pitted object by its neck and gently rocked it out of the damp sand. It was scratched, and the stopper was sealed tightly with wax. A rolled paper was clearly visible inside.

“Pirates!” Sarah cried, coming up from behind Bess.

“There are no pirates around here. For heaven’s sakes, Sarah. Well, I don’t think there are.” Bess held up the bottle and twisted it around and around, carefully examining it. The sisters looked at each other and Sarah said, “The Russians?”

“We’ve been at war in Crimea for a while now, but I don’t believe that Russian soldiers are tossing bottles with notes in them out onto the sea,” Bess said.

They carried their potential treasure up to the dry rock where their picnic awaited before scratching away the wax with the sharp edge of a mussel shell and gently prying out the cork. It popped out with a swoosh.

Bess plucked out the rolled-up paper with her fingertips. She unfurled it and slowly read aloud:

Agnes May Brewster

Born: July 1843. Colored slave.

She turned the bottle around, inspecting it from all angles.

“What does it mean?” Sarah asked. “Is it some kind of sign or omen?”

“Don’t be superstitious,” Bess ordered. She shook the bottle upside down, and a small carved heart tumbled out. She picked it up from the palm of her hand to closer inspect the tiny carved vines and little flower buds that wound around it.

“It’s clearly been carved to be heart shaped,” Bess said. “Although I’m not sure from what.”

“Really, we were meant to find this,” said Sarah. “I’m sure of it. It might be a sign. Or a message. Maybe from Mummy!” Her eyes widened at the thought of it. “That could be it. It could be from Mummy, couldn’t it?”

“I don’t think so, Sarah. Mummy is with the angels now.”

“Bess! How do you know that the angels aren’t over the sea?” Sarah asked.

“She’s my age,” Bess noted as she read the paper over again. “Born July 1843. Agnes May Brewster.”

“Do you think this is really from some colored slave?” Sarah mused. “Maybe she was lost at sea on a raft, surrounded by hungry sharks, and with her last bit of strength she tossed this bottle overboard with a note and the heart trinket, hoping to be rescued.”

“It’s possible. I don’t know, Sarah, I don’t know. We need to think about it, though. We can’t trust anyone with this. You cannot tell anyone, do you understand?”

“Yes, yes, of course,” Sarah agreed. “Maybe it is some sort of plea for help?”

“No. It doesn’t indicate anything of the sort. Of course, the good news here is that it doesn’t appear to be from the Russians,” Bess noted.

“Oh, Bess,” Sarah said hopefully. “I still think it could have something to do with Mummy.”

“Sarah, I wish that were so,” Bess said softly. “But I don’t believe that.”

Both girls took their time as they smoothed the rumpled note, touching the simple printed words and envisioning different possible explanations.

“Just think, Sarah. Imagine the adventures this little vessel has experienced. I almost wish I could stuff myself inside and be tossed back out to experience the world!”

After a while, they knew Mrs. Dow would miss them at home.

“We can’t take it back with us, Sarah,” Bess said.

“Snoopy Elsie will find it,” she agreed.

“Maybe. But even if I could get it back to the house and hide it, I’m afraid someone will see us coming back with it.”

“We could hide it in the bag,” Sarah suggested.

“Oh, and I suppose you think that Gertrude or Mildred would keep it a secret if they should find it? I hardly think so. Then I’d have to worry about getting it back out again undetected. It’s just safer to hide it here, away from Attwood. I’ll come back on my way to the library on Thursday and take it to show Chap. He’ll have a good idea where it’s from.”

“You think you can trust him?” Sarah asked.

“More than any adult I know, except Papa and Mrs. Dow,” Bess answered.

They pulled a few small rocks out of the headwall to create a little cave, above the high-tide mark where their newfound treasure would be safe from the rains, tides, and animals. They could come back again and safely examine it, but for now they needed to return home. They poured the tea out onto the ground, fed the biscuits to Sunny Girl, and hurried back across the fields and paths to the great stone house.

Chapter Eighteen

“I’d rather pretend we’re going to a fancy ball,” complained Sarah. Bess diligently wove chamomile flowers into her sister’s long dark braid before tying a handkerchief like a band around her own head.

“Any fool can get themselves off to a ball, Sarah,” Bess explained. “We are preparing ourselves for the true adventures that are going on in the world this very minute. We don’t know that Agnes May Brewster tossed that bottle overboard before she drowned. Perhaps she is living right now on a plantation in America as someone’s slave. There are all sorts of incredible things going on all over the world.

“But for today’s game, I have read about the native people called Indians living in the American West. They are a thieving, bloodthirsty group that paint their faces and go around practically naked, murdering the settlers.”

“The Indians are th

e natives?” Sarah asked, her brown eyes flickering.

“Yes, that’s what I’ve read,” Bess confirmed.

“Perhaps they aren’t happy with people coming and taking over their country, then. Maybe that’s why they are murdering and thieving. How would you like it if people landed their boats on the Isle of Wight and started taking everything over?”

“Well, I don’t know the whole story,” Bess answered. “And I don’t think I will until I am old enough to visit America and get the straight truth for myself. But until that day, we need to practice our skills. Here, put this around your shoulders and pretend it’s a sacred Indian blanket.”

Sarah stood draped in an old, frayed bed cover from their dress-up chest, her hair laced in white flowers with a feather sticking out of the top, reluctantly waiting for her orders. “Tomorrow can we play fancy ball?”

“Yes, yes, you goose,” Bess said.

“You’re not just saying that?” Sarah asked. “Last week we pretended every day that we were British soldiers fighting the Russians. Before that we explored India like Papa at least a hundred times. If I fight off a pretend tiger one more time I shall save it the trouble and kill myself! This week it is Indians every day, and now I can see slavery in my future. I’m tired of all this violence. I want to play fancy ball. Do you promise?”

“Yes, I promise,” Bess said. “And may I remind you that we are still at war with the Russians in Crimea. You’ll be glad some day that you were prepared, should the Russians defeat our boys and decide to land on our little island next.”

“Could such a thing happen?” Sarah asked.

“Who knows in this world.” Bess tucked a pretend knife in her belt and slung a branch shaped like a rifle over her shoulder. “I’ll put my head down now and count to ninety-nine. You go off somewhere and hide. Don’t make it too easy. I’m the scout, and I’m going to track you down.”

Sarah’s eyes narrowed. “And then what will you do to me when you find me?”

Currents

Currents